An Article That Is Written by a Journalist and Reviewed by Editors Is Referred to as

The New York Times opinion editor James Bennet resigned recently after the paper published a controversial stance essay by U.Due south. Sen. Tom Cotton fiber that advocated using the armed services to put down protests.

The essay sparked outrage among the public equally well equally among younger reporters at the paper. Many of those staffers participated in a social media entrada aimed at the paper'due south leadership, request for factual corrections and an editor's note explaining what was wrong with the essay.

Somewhen, the staff uprising forced Bennet's departure.

Cotton's column was published on the opinion pages – not the news pages. But that's a distinction often lost on the public, whose criticisms during the recent incident were often directed at the paper as a whole, including its news coverage. All of which raises a longstanding question: What'south the deviation between the news and opinion side of a news system?

It is a tenet of American journalism that reporters working for the news sections of newspapers remain entirely independent of the opinion sections. Only the dissever betwixt news and stance is not as clear to many readers as journalists believe that it is.

And because American news consumers have get accustomed to the platonic of objectivity in news, the idea that opinions bleed into the news report potentially leads readers to suspect that reporters have a political agenda, which damages their credibility, and that of their news organizations.

How news and stance grew apart

Long before newspapers became institutions for collecting and distributing news, they were instruments for the personal expression of individuals – their owners. There was little thought given to whether or non opinion and fact were intermingled.

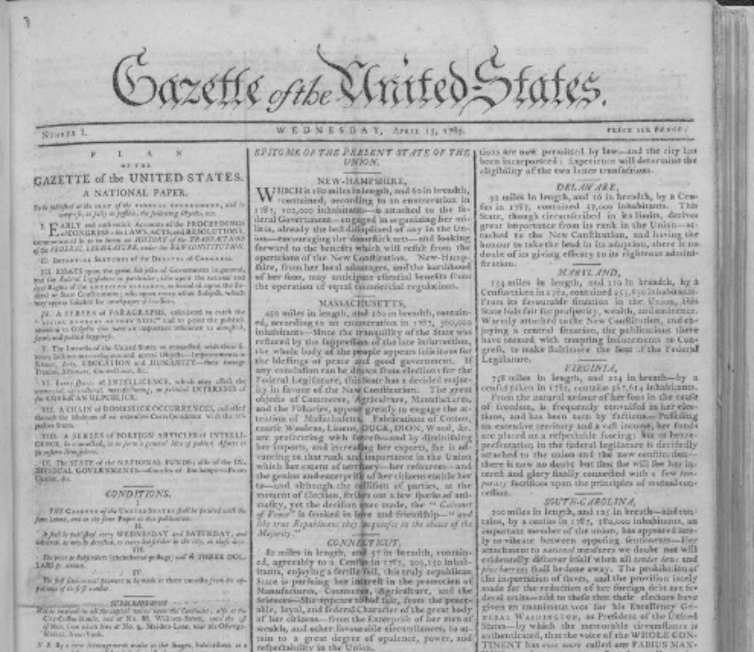

Benjamin Franklin ran the Pennsylvania Gazette from 1729 to 1748 as a vehicle for his own political and scientific ideas and even only his twenty-four hours-to-twenty-four hour period observations. The Gazette of the U.s., first published in 1789, was the nigh prominent Federalist paper of its time and was funded in function past Alexander Hamilton, whose letters and essays information technology published anonymously.

In the early 19th century, newspapers were often nakedly partisan, since many of them were funded by political parties.

Over the course of the 19th century, though, newspapers began to seek a popular audience. As they grew in circulation, some began to emphasize their independence from faction.

Coupled with the rising of journalism schools and press organizations, this independence enshrined "fact" and "truth" every bit what scholar Barbie Zelizer calls "God-terms" of journalism by the early on 20th century.

Paper owners never wanted to give up their influence on public opinion, yet. Every bit news became the main product of the newspaper, publishers established editorial pages, where they could continue to endorse their favorite politicians or push for pet causes.

These pages are typically run by editorial boards, which are staffs of writers, oftentimes with individual areas of expertise (economics or strange policy or, in smaller papers, state politics), who typhoon editorial essays. They are and so voted on by the board, which usually includes the publisher. They're then published, commonly with no author attribution, every bit the official opinions of the newspaper. There are variations on this process: Ofttimes the editorial board will make up one's mind on topics and the paper'due south opinion before these writers go to work on their drafts.

James Bennet, The New York Times opinion editor who resigned, best-selling in an article on the newspaper'southward website that was published in January 2020, months before the Cotton essay, that "the role of the editorial board tin can be disruptive, particularly to readers who don't know The Times well."

Through near the 20th century, newspapers reassured their readers and their reporters that at that place was a "wall" between the news and opinion sides of their operations.

Publishers relied on this thought of separation to insist that their news reporting was fair and independent, and they believed that readers understood that separation.

This is a specially American style of operating. Readers in other countries usually expect their newspapers to accept a bespeak of view, representing a particular party or credo.

The creation of the op-ed page

One manner that newspapers found to allow a greater range of opinion in its pages was to create an op-ed page, which publishes opinions by individuals, not those of the editorial board. As journalism historian Michael Socolow recounts, John Oakes, the editorial page editor of The New York Times in 1970, created the get-go op-ed page because, he felt, "a paper most effectively fulfills its social and borough responsibilities by challenging authority, acting independently, and inviting dissent."

"Op-ed" is short for "opposite the editorial page," non "opinion and editorial" or opinions that are opposite from those of the editorial folio. Literally, the name comes from the fact that it was located across from – opposite – the editorial folio in the impress paper.

The op-ed page of a print newspaper typically includes the paper's opinion columnists. These are employees of the paper who write regularly. The paper also ordinarily publishes a selection of opinion pieces from outside writers. Newspapers around the country emulated the Times after the op-ed page debuted.

Online opinions, changing norms and blurred lines

With the expansion of opinion pages online, the Times was publishing 120 opinion pieces a calendar week at the time of James Bennet's resignation.

While the move online allows The New York Times op-ed page to vastly increase its output, it likewise creates a trouble: Opinion stories no longer look conspicuously different from news stories.

With many readers coming to news sites from social media links, they may not pay attention to the subtle clues that marking a story published past the opinion staff.

Add to this the fact that fifty-fifty readers who go to a paper'southward homepage are met with news and opinion stories displayed graphically at the same level, connoting the same level of importance. And reporters share analysis and opinion on Twitter, further confusing readers.

The news sections of the newspaper likewise increasingly run stories that incorporate a level of news analysis that casual readers might not be able to distinguish from what The New York Times designates as opinion.

In 1970, when the op-ed page debuted in The New York Times, daily newspaper circulation was equivalent to 98% of U.S. households. By 2010, that number had dropped below 40% and has connected to dip since then.

Even if readers in 1970 could clearly differentiate between news and opinion, they likely do not accept the same level of critical engagement when news exists online and in almost unmanageable book.

If news organizations such as The New York Times go on to maintain that a robust opinion department, separate from their news reports, serves to further the public conversation, then those institutions volition need to practise a better chore of explaining to news consumers where – or if – the "wall" between news and opinion exists.

[You lot're smart and curious near the world. So are The Chat'due south authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter.]

Source: https://theconversation.com/journalists-believe-news-and-opinion-are-separate-but-readers-cant-tell-the-difference-140901

Post a Comment for "An Article That Is Written by a Journalist and Reviewed by Editors Is Referred to as"